In Celebration of its 150th anniversary, Holland America Line is partnering with The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. The collaboration will commemorate the cruise line’s beginnings as immigrant carrier with on-board content and a curated exhibit at Ellis Island.

Holland America Line will partner with The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, the non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the eponymous landmarks, to celebrate the cruise line’s 150-year journey from immigrant carrier to consumer ocean liner fleet. The partnership, which kicks off October 26 as Holland America Line completes the recreation of the brand’s first-ever sailing from Rotterdam to New York City, features on-board video content across Holland America’s entire fleet produced by an Ellis Island researcher, as well as a curated exhibit launching in 2023 at Ellis Island detailing the brand’s historical prominence in bringing 1 in 10 immigrants from Europe to the United States.

“Our history is deeply woven within the fabric of America’s story,” said Gus Antorcha, president, Holland America Line. “It’s only fitting that as we celebrate this milestone anniversary, we partner with the entity responsible for restoring and preserving Ellis Island, the entrance to America that so many of our passengers experienced on their journey to a new start.”

The collaboration will launch with a joint talk between Stephen Lean, director of The American Family Immigration History Center at Ellis Island and Bill Miller, noted cruise historian, detailing the immigrant experience in the late 1800s; the presentation will be available on-demand across all ships within the fleet. Noting the cruise industry’s – and particularly Holland America Line’s – importance in the immigrant journey from Europe to US, the Foundation will curate an exhibit in its History Center available for visitors from February to April 2023.

“We are excited and proud to partner with Holland American Line to celebrate the line’s impact on Ellis Island history and the U.S. immigrant experience,” said Jesse Brackenbury, president and CEO of The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. “Holland America Line’s relevance is reflected daily at our Family History Center where historic ship images adorn the walls and visitors learn about their ancestors’ journey to America. We look forward to a longstanding collaboration.”

Holland America Line’s impact on immigration

The cruise line, which was founded in the Netherlands in 1873 as the Netherlands-American Steamship Company, was primarily a carrier of immigrants from Europe to the United States until well after the turn of the century, carrying nearly 2 million passengers to new lives in the New World.

On the first voyage the first Rotterdam ship – which departed the city of Rotterdam October 15, 1872 – transported 10 cabin passengers and 60 ‘between-deck emigrants’. Most cabin passengers were probably Dutch; most of the steerage emigrants were probably non-Dutch. Part from the passengers, crew on the maiden trip from Rotterdam were one captain and 43 crew members, consisting of the forward crew and the engine room crew aft. The number of crew members differed slightly per trip, depending on the number of passengers.

Emigrants from the Netherlands were often poor farm workers with large families who fled their poor conditions of poverty and unemployment, hoping to find work and a good life in the New World. There were also those who left for reasons of faith, especially from the Dutch Reformed house, who went to found their own ‘undisturbed’ church abroad. The emigrants also often came from Eastern Europe, in the hope and expectation that they would have a better life in the New World than in their region of origin.

Between 1873 and 1914, 31,835 immigrants came from Russia, 5,403 from Austria, 4,391 from Hungary, 2,224 from the Netherlands, 1,446 from Germany, and 3,717 from other countries. Three quarters of those immigrants sailed with Nederlandsch-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij, now Holland America Line.

The first-class cabin passengers paid fl. 65 (or $36) for their crossing to New York. Converted into today’s currency this equates to approximately €3,385 (or US$3,405). The price of an emigrant ticket ranged from fl. 36 (or $20) to fl. 45 (or $25), which in today’s currency (2022) equates to approximately €1,875 (or US$1,895) and €2,345 (or US$2,365).

An immigrant’s life on board Rotterdam I

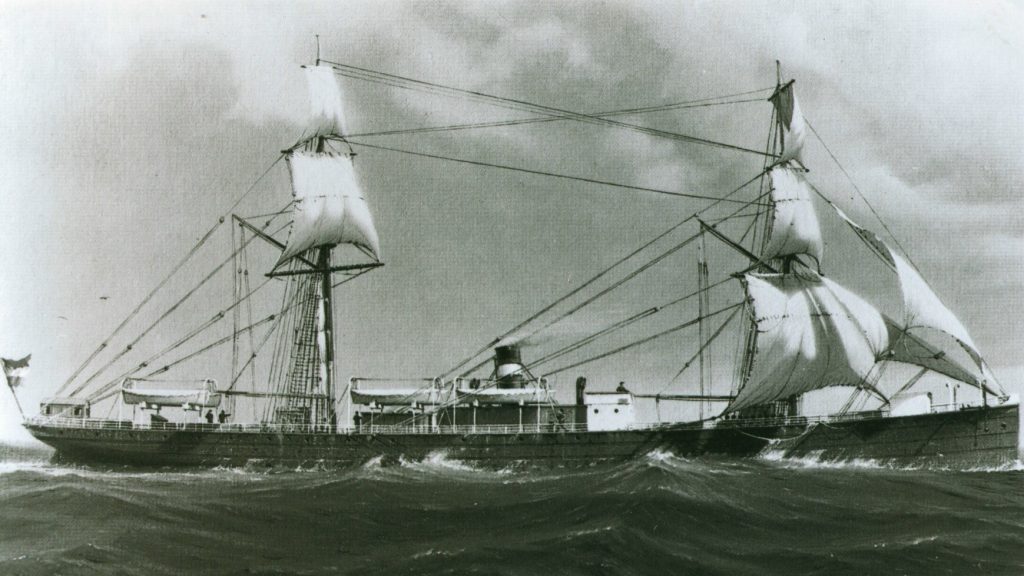

Compared to today’s modern cruise ships the dimensions of Rotterdam I were very modest. It was 81.84 meters long and 10.9 meters wide. By comparison, Holland America Line‘s new Rotterdam VII is 300 meters long and 35 meters wide. Ordered as a steamship, Rotterdam I was constructed of iron with two full decks. The ship also had extensive options for using sail and could therefore be rigged as a brig with 10 sails. The sails were often used when the wind was blowing in the right direction, saving coal and/or helping to maintain higher speeds.

The ship was christened by the daughter of Captain Hus, and the first crossing from the Netherlands to New York in 1872 was an arduous Atlantic crossing that took 14 days and 6 hours.

On Sept. 26, 1883, the ship stranded on the Zeehondenbank near the Dutch Island of Schouwen. Then the weather turned and the abandoned ship broke into two pieces on October 12 due to the pounding waves. Eventually the hull disappeared under the sea.

Two classes, different service

The first steamship Rotterdam had only two classes that were strictly separated. There was standard accommodation for 8 to 10 (first-class) cabin passengers and for about 500 (third-class) ‘between-deck emigrants’. There was no mixing or social interaction between first- and third-class passengers. First-class had accommodations on the upper deck in the midship deckhouse in cabins and a cabin/salon. Third-class had Spartan accommodation in lofts under the spar deck (a spar deck is located above the main deck) along the sides of the hull, and on the steerage in large common areas that functioned as lodgings and dormitories.

The first-class cabins were ‘comfortably’ furnished with a comfortable bed (a ‘cage’ in ship’s jargon) and an armchair, washbasin with night mirror, an ordinary cosmetic mirror, a candlestick and an oil lamp. The cabin also contained a water carafe with a drinking glass, sheets, a pillowcase, towels, a cage curtain, and a porthole curtain. No light or open fire was allowed in the hut after 10 o’clock in the evening. Smoking was also not allowed in the cabin. The cabin passengers ate their meals and recuperated in a ‘comfortable’ cabin, also known as ‘the saloon’. In addition to a large table with extensions, there were also four benches (with loose cushions), a sofa (with cushions and ‘state curtains’) and a sideboard with mirror. There were two hanging lamps, two stoves and a sign for glassware.

The third-class consisted of large, sporadic and poorly ventilated areas for 6 to 12 people under the spar deck or partitioned areas for 20 to 40 people on the steerage. Due to the inadequate population register and the personal data submitted from it, it was not possible to determine who was ‘really’ married. The shipping company did not take any risks in that regard. Men and women were strictly kept from each other in separate rooms. Married couples with children were housed with peers. However, they were completely separated from the accommodations for the men and/or women. The emigrants had to bring their own blankets and eating utensils. The cages, which were sometimes stacked up to four high, could usually only be reached via the foot end, because there was usually little or no space between the cages.

A different culinary experience

Part from a difference in accommodations, passengers on board Rotterdam I also received a different culinary experience during the crossing. First-class passengers were offered a meal in the saloon four times a day: breakfast at 10 o’clock in the morning (barley, meat and fish with bread and tea); coffee at noon (on Sundays and Wednesdays interspersed with chocolate milk); dinner at 4 o’clock in the afternoon; and at 8 o’clock in the evening ‘bread and tea’ (if desired). Usually a cow, some sheep, chickens and ducks accompanied the ship. They were the suppliers of milk, meat and/or eggs respectively. Feed and hay were taken on board for these animals.

The ‘between-deck emigrants’ were fed from the galley without further ado; probably three times a day: in the morning breakfast (barley), in the afternoon a ‘hot meal’ and in the evening at 6 o’clock ‘supper’ (bread with tea). They ate at simple tables with benches next to their sleeping places. The steerage guards distributed the food. In good weather a meal was served outside on deck, guards scooped the food from large cauldrons onto the plates of the passing emigrants. These people then went down again with their plates.

Eventually Holland America Line was the first to do away with Steerage Class altogether, renaming it Emigrants Class where unlike the competition, guests were served three square meals.

It is this level of care and attention to detail – a tradition and hallmark of the brand that has continued to this day – that was the impetus for its nickname at the time: The Spotless Fleet. Holland America Line provided everything from doctors and a pre-departure hotel complete with English lessons and classes on American civics to ensure passengers a safe journey to New York; and in fact, 99% of the immigrants carried on the fleet were cleared for entry through Ellis Island, a tremendous feat at the time.

Holland America Line began the recreation of its first voyage with a sendoff October 15 from the Netherlands. The ship will sail past the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island as it arrives in New York City around 7am October 26.